Reducing Labor Costs without reducing FTE's

Charlie Dawson, MBA, CPC, President, Workforce Prescriptions

Kathy Brodbeck RN MS NEA-BC,VP Operations & CNO, St Peters Health System

Nora Baratto MSW, Dir Case Management, St Peters Health System

Thea Dalfino, MD, Chief of Hospitalists Services, St Peters Health System

Keith Bush

Chief Information Officer

Workforce Prescriptions

Original Unmodified Word Document Can Be Viewed By Clicking Here

An updated to the Labor Utilization Audit Case Study

Charlie K Dawson, MBA, CPC

President

Workforce Prescriptions

"Quality & Quantity have LESS to do with profitability than Efficiency does!"

One of the most brutal truths of healthcare is encompassed by the quote above that I ripped from my subconscious not too long ago when faced by a client asking the question, "Why do you focus so heavily on changing HOW we do our work?". My off-the-cuff response was that (now infamous) statement about quality, quantity and efficiency printed above.

The CEO in question paused and said, "Let me think about that . . . you can have great quality and be unprofitable, you can have huge volumes and still lose money and you can even have huge volumes with great quality and not make ends meet. So if I'm hearing you right, what you are saying is that once you are efficient, quality and quantity become enhancements to profitability, but have little to do with profitability on their own!"

I nodded in assent, but had truthfully never considered it in that way. Quality and Quantity enhanced profitability only if the organization is first efficient enough to take advantage of them . . . TRUE! The quality argument is analogous to buying the best car in the world, consequently not being able to afford the gas. The quantity side compares well to selling a product below cost – the more you sell, the more you lose. Who on earth would ever believe a winner arises out of those business models?

These are concepts I have spent years trying to articulate with varying degrees of success yet none of my attempts has been as concise or readily understood as that single CEO's contemplative statement that ties both concepts up into a nice bow.

Lines in the sand . . .

The biggest battles in healthcare nearly always come down to conflicts between efficiency and quality.

How much efficiency is "just enough" and how much is "too much"?

Who defines "quality" and how do we measure it?

These conflicts occur nearly universally in contemplating changes to length of stay, even though the value proposition is on the side of efficiency.

There are two clear teams and they each have their slogans:

- One team says, "With better than 95% of our reimbursements being case/DRG rate payments, it behooves us to become as efficient as possible in driving care since each hour of LOS reduction represents $2.94M per 100 staffed beds in direct expense and labor savings".

- The other team counters with, "If we push care progression too far/too fast we risk reductions in clinical quality and potentially increase our rate of avoidable readmission".

As a result, in 2009 and year-to-date 2010 as a part of our ongoing efforts to increase labor efficiency, we have focused as a collective (consultants and St Peter's healthcare leaders) on a single major opportunity: Improving Care Efficiency in order to reduce length-of-stay and to gain the associated labor value such improvements represent. This meant we have had to work to accomplish 4 distinct outcomes:

- Developing a standard admission processes

- Standardizing "high volume" order sets

- Fostering 100% compliance to the development of working DRG's and target discharge dates for ALL patients

- Prioritizing care around target discharge dates

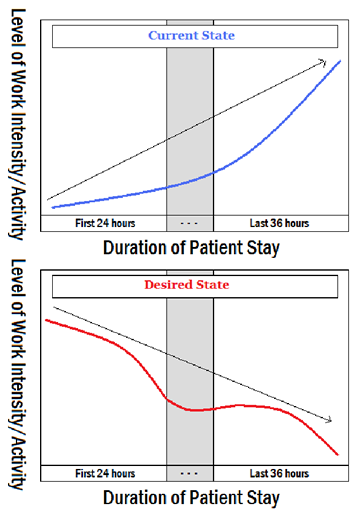

Late in 2009, in order to more ably communicate these goals, as a group, we developed a pictogram intending to illustrate "how" and "why" our care management and prioritization was less than ideal. We were pleasantly surprised by how exceptionally well that one picture functioned as a major touch-point to drive rapid progress in our pursuit of change.

So our new theme for 2010 became: "Focus on redistributing work intensity to the front end of each patient's stay" (See graphic below). Using this theme as our central focus proved to be the key to driving deep, meaningful changes that produced the balance of our desired results.

In Care Efficiency and its associated LOS, this picture allowed: physicians, nurses & case management to focus on a shared goal for change: namely – move the bulk of the work forward in the patient's stay.

This "shared view" has been lacking in 2009 efforts resulting in each group "implementing in a vacuum" which has held back overall progress as each constituency jostled forward, then back again in response to each other.

In Care Efficiency and its associated LOS, this picture allowed: physicians, nurses & case management to focus on a shared goal for change: namely – move the bulk of the work forward in the patient's stay.

This "shared view" has been lacking in 2009 efforts resulting in each group "implementing in a vacuum" which has held back overall progress as each constituency jostled forward, then back again in response to each other.

It has allowed all three key groups to "suddenly" recognize "Why" assigning working DRG's & target discharge dates, enhancing concurrent review, prioritizing care/orders and developing standardized order sets are necessary and more importantly, it assists the organization to visualize "what the value" of these changes represents to patients, staff and the larger organization.

In scheduling, this picture allowed: department managers to recognize that discreet work volumes WILL BECOME more predictable (on a 2-12 hour basis) and allow for greater prioritization. In addition to the effect of the newly discovered touch-point, work continues on the development of a nursing-centric scheduling management tool that provides access to needed information in an accurate and timely manner. The initial system provided by WRX accomplished its designated task and has effectively elevated the desire by managers for a "better" system. Such a system has now been developed and is currently in the processes of being "coded" into stand-alone software. This tool is expected to be completed by June 2010.

In Staffing & Workforce flexibility, this picture allowed: nursing leaders to continue to more clearly understand "what" work is intended to produce (starting with the end in mind) and "why" individual tasks and work processes need to be developed to be as predictable and flexible as possible. This assists the organization to continue to pursue it's three main "portability/flexibility" initiatives in 2010:

- Growth of cluster specific internal staffing pools

- Implementation of forced vertical hiring cascades

- The rigid compliance to experience level hiring standards

As a majority of the original case study was didactic in nature, as a group, we determined that it was important to see the change we are creating through the eyes of some of its key participants. What follows are two (2) distinct narratives describing the changes to understanding and process we have achieved. These narratives were written in order to allow followers of the case study to "view" the level of leadership required, change endured, commitment illustrated and effort undertaken to replicate the enormous results produced.

A simple example: During the recent pilot of our new care delivery model on a combined patient population of 85 medical/surgical beds, we were able to reduce LOS 28.3% in a 2 week period.

| Unit A: | 6.43 to 4.44 days |

| Unit B: | 5.33 to 4.0 days |

| Unit C: | 5.77 to 4.1 days |

Other accomplishments were seen as well:

- The number of avoidable readmissions was significantly reduced due to improved case escalation.

- Denials associated with discharge planning were reduced

- Staff re-energized, improved job satisfaction.

- 100% compliant with Medicare's Important Message

- Only 4 readmissions within 30 days

Dir Case Management

St Peters Health System

As Director of the Case Management Department, I have always been very passionate about implementing a multi-disciplinary rounds process throughout the hospital. Many years ago, while working at a nursing home, I had seen the benefits first-hand. The team met once a week to discuss each patient's plan of care and make any changes. Patients and families were active participants, driving the plan by stating their needs and preferences. The communication was excellent and the team got to know each patient as an individual.

In an acute care environment, I knew the challenges would include engaging team support and enthusiasm around meeting times, securing physician / hospitalists involvement, developing an efficient process and hard-wiring it.

In 2008, many barriers both internally and externally, began to increase hospital length of stay (LOS), The Case Management Department was struggling to stay afloat because of the added responsibilities that were placed upon us. New CMS quality initiatives, increased barriers to discharge, increased patient acuity, scrutiny from payers and budgetary constraints were gradually making it very difficult to "keep all the balls in the air". Staff satisfaction in the department was at an all-time low; overwhelmed in their role, not feeling effective or efficient, our most experienced staff started leaving and it became increasingly difficult to meet key department outcomes like reducing LOS, managing readmissions and ensuring patients are in the appropriate level of care. Each of these key metrics had a direct impact on ensuring quality patient care and the financial well being of the hospital.

In many hospitals, the perception is Case Management Departments are responsible for reducing LOS, but LOS is not just a Case Management Department problem. It belongs to the multi-disciplinary team and only together will it be fixed. The challenge was to get other departments to see and understand they are an integral part of the solution.

In 2008, the Case Managers and nursing units worked together to establish a regular rounding process on each of the units. There was a wide variation of how rounding should occur at the bedside, in the patient room or meeting room. Some units wanted to discuss every patient while others only wanted to discuss patients for discharge. Some units developed tools and others were worried about who was responsible for completing the tools. The time it took to complete rounds was frustrating to a lot of disciplines and participation was inconsistent. Additionally, we had no real physician support or leadership. All hospitals know that one of the most important keys to successful outcomes is active physician participation. Some say timing is everything and in our case this was especially true. A new VP of Medical Affairs just started at the hospital and was very eager to become actively involved in developing a close collaborative relationship with Case Management, Nursing and the Hospitalists.

Leadership support was essential to implementing multi-disciplinary rounding throughout the hospital. To get the process started, Case Management leadership met several times with the Vice President of Operations, Vice President of Medical Affairs, Director of the Hospitalist Group and the Nursing Directors / Managers to discuss the process. The leadership team jointly defined the essential components the rounding process. These included: real time focus on the safety and effectiveness of care on each patient, identification of the working DRG / expected LOS for the patient, proactive identification of the Present On Admission indicators, examination of key quality indicators to prevent hospital acquired conditions, addressing potential barriers to care that impede discharge. For example; are patients being ambulated, families are aware of discharge time for transport and are physicians identifying intent to discharge to the team. The next step was to set expectations about the rounding process to the hospitalist group, nursing and case management. Other disciplines could participate if they wanted but it was decided that it was important to establish a good structure and process.

As the director of the Case Management Department, I was fortunate to have the ability to assign a very seasoned case manager with excellent team building skills to lead this initiative and be the primary point person for the hospitalist. This case manager was a wealth of knowledge to the physicians and collaboration among all three disciplines began to nicely occur. As rounds progressed, a hard wired process began to emerge. There was a time keeper, staff came prepared, and a quality rounding tool was used to remind our selves of the key issues we needed to cover on each patient and only complex patients with d/c needs were discussed. As rounds progressed, other disciplines such as Pharmacy and Physical/Occupational Therapy, who were previously very strapped for time, became very curious and joined rounds on a regular basis.

As with any new or developing process, the "honey moon" phase of rounding was over. In acute care, there are multiple competing priorities and what ever one is deemed most important on any given day gets your focus. The Hospitalist and Case Management Department had staff shortages and the hospital was experiencing surges in admissions. Participation again began to wax and wane. Much to our amazement, LOS had decreased by a half day. This gave us all a flicker of hope and ignited the spark of enthusiasm we needed to keep the process going. How can we make this process better for everyone?

Ongoing discussions about the rounding process occurred. Some hospitalists were not receptive to unit based assignment as a means to provide greater continuity for the patient and units. Hospitalist preferred going from unit to unit with an assigned case manager. The Nursing and Case Management staff liked the unit based model, citing the close proximity of the Hospitalists as the biggest factor. Hospitalists would be able to meet with patients and families and plan for intended discharge. In 2009, both of the models were trialed. Hospitalists LOS decreased to 5.78 for the trial period from 6.67. However, having each Hospitalist staffed with a Case Manager is cost prohibitive. The rounding process had come too far along to let this debate impact what had been achieved.

Simultaneous to the unit based verses hospital based debate, Case Management leadership met with the Vice President of Operations and a consultant to discuss the Case Management Department growing job dissatisfaction. The department met and completed an assessment of all the new regulations and barriers that currently impacted us, changes in staff roles and responsibilities and solutions for change. What the department staff identified was the functions of discharge planning and utilization management had become extremely time consuming, complex and staff roles have become highly specialized. The obvious solution was the roles needed to be separated out so we could focus on each area as each function impacted the hospitals bottom line.

Additionally, what we realized was everyone within the team is focused on completing their own individual pieces of patient care that no one is looking at the whole picture and in order to impact LOS we needed the case manager to focus on driving the plan of care with the whole rounding team. In order to do this the department needed more resources to implement the new structure.

Asking for additional resources in the current economic climate would be difficult. However, with the unwavering support of our VP of Operations and consultant (WRx) we devised a plan. In order to demonstrate the relationship between the need for more resources and LOS, On March 1, 2010, to the Case Management Department piloted the new roles on three medical/surgical units for two weeks to demonstrate the impact. We separated the Utilization Management function from Discharge/Care Manager function to promote patient focused care. The new roles created were:

- Care Manager

- The Care Manager (CM) identifies patient's LOS, completes the initial Assessment, assigns a Discharge Planner (DCP). The CM ensures the Plan of care is progressing and leads the multi-disciplinary rounds.

- Discharge Planner

- The Discharge Planner (DCP) is responsible for implementing the discharge Plan, meeting with patients/families, and making appropriate referrals.

- Utilization RN

- The Utilization RN's (UMRN) completes clinical insurance reviews; makes sure appropriate documentation is in place to minimize denials and interacts with onsite payers. The UMRN obtains authorization from insurance providers, and makes certain patients are at the appropriate level of care and in the right status.

- Case Management Assistants

- The case management assistant's roles are to assist the team in send patient referrals, nursing home returns, and documentation in Allscripts that key tasks like the CMS 48 hour notice is documented and faxing or copying. Pilot Structure

- Strict interdisciplinary process: walking AM rounds with Nursing, Hospitalists, Care Managers and Ancillary staff.

- Hospitalist were united based on the 4th floor.

- Clearly defined team member roles and expectations.

- LOS expectation communicated to the team, Milliman Care Guidelines listed on the chart, projected discharge date reviewed daily.

- Case Management staff to huddle at the end of shift to review the outcome of the day's goals.

- Care Manager complete assessments, determine discharge plan, and identifies to the team the expected LOS for the patient. Refers cases to Discharge Planners to implement and expedite discharges

- Bedside RNs to actively participate in interdisciplinary rounds utilizing the Workstation On Wheels (WOWs) at bedside. Collaborates with care manager to ensure testing and consults are moving along and ensuring quality measures are met as well as patients are being ambulate and foley or tubes are being removed as soon as possible.

- Hospitalist are actively identifying intent to discharge and being proactive in completing required D/C summary or D/C forms a day prior to D/C.

- The number of avoidable readmissions was significantly reduced due to improved case escalation.

- Denials associated with discharge planning were reduced.

- Staff re-energized, improved job satisfaction.

- 100% compliant with Medicare's Important Message.

- Only 4 readmissions within 30 days.

- The active participation of leadership working collaboratively with staff made them and there opinion feels valued. It also communicated to all interdisciplinary rounding is an expectation.

- Leadership at all levels became involved and interdisciplinary effort became the norm. Silos were eliminated.

- Focused responsibility promotes increased patient satisfaction and quality transition across the continuum of care.

- All disciplines would benefit from a case escalation process.

- Only adequate Hospitalist and Case Management staffing can achieve the positive outcomes of this model.

The rounding structure was enhanced

Reduced LOS on the combined 4th floor units to 4.2 days

| Unit A (4McAuley): | 6.43 to 4.44 days |

| Unit B (4 NR): | 5.33 to 4.0 days |

| Unit C (4 Gabrilove): | 5.77 to 4.1 days |

Important Learning's from Pilot

Chief of Hospitalist Services

St Peters Health System

Most of the hospitalists vividly remember the days of having at least 5 patients on our daily rounding list that had no active medical issues and were simply waiting for placement. They were our favorite patients because they were quick to round on and had very few medical problems that needed to be managed. Since the implementation of multidisciplinary rounds, those days are long gone, as are those patients.

When the idea of multidisciplinary rounds was presented to the hospitalist group in 2008 as a means to decrease the hospital's length of stay, we were skeptical but willing to give it a try. The hospitalist literature at the time was touting the benefits of a teamwork approach, but more as a way to improve the quality of patient care rather than a system designed to cut costs. However, we had our reservations about how much we, as physicians, could impact length of stay. The majority of the hospitalists believed we were already discharging patients in a timely manner but that we weren't getting enough case management support for patients waiting for rehab and nursing home placement.

The first trial of multidisciplinary rounds for the physicians occurred three days per week from October 2008 to April 2009. It consisted of each rounding hospitalist presenting their ~20 patients to a team of care providers for 15 minutes. This team included representatives from case management, social work, physical and occupational therapy, and pharmacy. The physicians would briefly present the major medical problems of the patient and the group would discuss a discharge plan (ie. where will the patient go when they leave, do they need homecare, are there any barriers to discharge). Based on simply meeting three days per week, the hospitalist length of stay dropped from 6.67 days to 6.16 in 4Q-08 (with a rise in the expected LOS).

Although the program had some success with reducing length of stay, there was dissatisfaction with the process from some of the major parties involved. The hospitalists still believed they had not changed how they were practicing medicine, but felt the majority of the LOS reduction was due to the case managers now being held accountable for getting patients discharged in a timely fashion. The physicians also felt that taking 15 minutes in the middle of their busy day was an inconvenience. Sometimes one physician would show up late, and that would push everyone else behind. From a process standpoint, the physicians were concerned that the only discussions being held were about discharge and very little was presented about how to provide better quality of care while the patient was still in the hospital. The non-physician members of the team were frustrated by having to take an hour and a half out of their day to go through each physician's patients. Everyone knew there were opportunities for improvement.

One of the proposals from case management involved geographic rounding. The hospitalists were very reluctant to try this house-wide and insisted on trialing it on one floor first. The hospitalists' believed they would have the most success if each rounding team was paired up with a designated case manager, rather than being isolated on one floor. Hospitalists, in general, choose this field because they like the variety of medical problems encountered on a daily basis. Several physicians worried that they would be stuck treating only respiratory, cardiac, or cancer patients all day and wouldn't see the diverse patient population they had come to enjoy working with.

As a compromise, in May of 2009, we moved two hospitalist physicians to the fourth floor (three medical/surgical units) and designated one hospitalist to care for patients throughout the hospital and pair up with one case manager. With the geographic rounding model, it was a challenge to assign patients on the fourth floor to only their designated teams, as the daily hospitalist census varied dramatically and the physicians in the group preferred all six rounding teams to have approximately the same number of patients. Another obstacle we encountered with geographic rounding was determining what to do with patients who transferred from a telemetry floor to the fourth floor. Would the hospitalist on the fourth floor or the hospitalist that had been following them on the telemetry floor now care for that patient? The physicians decided that continuity of care was most important, and the non-4th floor hospitalist would see the patient.

The new model for multidisciplinary rounds on the fourth floor involved the same members as the previous model, except the nursing team leader was present, rounds were expanded to 5 days per week and the patients were discussed in much greater detail. More attention was brought to foley catheters, central lines, ambulation status, and fall risk. With this new model, the length of stay continued to drop, with a LOS of 5.78 for 2009.

For the one team that had a hospitalist and case manager that covered the same patients throughout the hospital, the physicians were pleased with this arrangement. The hospitalist and case manager met every morning to discuss the plan for all the patients on that hospitalist's list. It allowed the hospitalist to see a variety of patients while still working closely with one case manager. The hospitalist always knew who to call for discharge issues, and knew who to tell patients to contact if they had questions about their discharge. Unfortunately, the case management department became understaffed, that case manager was no longer available to round with the hospitalist, and the trial was abandoned.

Initially after implementation of geographic rounding, the hospitalists assigned to the fourth floor had mixed reviews of the system. Some of the benefits for the hospitalist included receiving less pages, being more accessible to families and patients, being able to see patients more than once per day and update them on the results of studies and tests that came back throughout the day, having greater interaction with the nursing staff, and spending less time walking around the hospital. However, what some physicians saw as advantages, others saw as drawbacks. Although they were getting fewer pages, the physicians were constantly interrupted by nurses approaching them while they were trying to write notes or read charts. The doctors felt there was nowhere to go to get away from patients' families and nurses to be able to get their work done. Some hospitalists complained about the monotony of dealing with only cancer patients, or only pulmonary patients. Another issue was the fact that the non-fourth floor hospitalists who had become accustomed to multidisciplinary rounds and frequent interactions with case management and PT/OT were now put back in the original system in which they had to track down a case manager if/when they needed one. They found the old system to be very inefficient. The one thing everyone could agree on was that there was a more teamwork focused approach on the fourth floor and having all members of the care team on board with the management plan streamlined patient care.

For much of 2009 the hospitalists had difficulty getting one hospitalist team assigned to the fourth floor wings as had been outlined. It wasn't until we had a meeting with the patient flow manager that things became somewhat easier. It was proposed that one unit (4 NR) become solely a hospitalist floor. With the flow manager prioritizing hospitalist patients to the 4th floor, the hospitalist census increased on 4NR to the point where we were able to assign one doctor to 4NR, one to 4 McAuley, and one to 4 Gabrilove. Multidisciplinary rounds continued on these floors until November 2009 when case management lost several members of their department and were no longer able to participate.

However, the hospitalists felt we'd made a lot of progress during that time and were interested in continuing the process on 4 McAuley. Daily rounds were moved from a conference room to door-side rounds out in the hall to encourage the bedside nurses to attend. Patients were discussed in more detail, including their current ambulatory status, how well they're eating and drinking, any social issues, and barriers to discharge. By incorporating the bedside nurses, the physicians could give verbal orders for anything the nurse needed and the nurse could inform the physician of any critical lab values or changes in the patient's status overnight. Although this system brought together even more members of the care team, it was the only floor in the hospital that had the physicians working closely with case management and nursing on a daily basis.

In January of 2009, the hospitalist census rose dramatically, to over 150 patients. The average daily census for 2009 was 110 patients. There were days when individual physicians were responsible for upwards of 25 patients. This led to less documentation of co morbid conditions and severity of illness and an increase in the LOS.

Fortunately, around that time the case management department devised a strategy to change the roles of the case managers and increase their staffing on the fourth floor for a 2 week period in early March. In addition to the staffing changes, we all sought to optimize multidisciplinary rounds and assign everyone roles. The case manager was responsible for educating the physician and multidisciplinary team on the target LOS for various conditions and setting a goal date of discharge for every patient. The physician briefly discussed their medical management of each patient and assigned tasks to the case managers and nurses (ie. The case manager would be responsible for contacting the family for certain issues, the nurses would be asked to call a consultant and ask them to stop by earlier in the day to facilitate a discharge, etc). PT/OT was also present to discuss what type of rehab needs a patient may have. Spiritual care attended the rounds to have a better understanding of which patients he would best be able to help. The nursing team leaders were responsible for updating the physician on any changes overnight, notifying them of any medication/IVF renewals, discussing if the patients had central lines or foley catheters and for ensuring that the patient received the imaging, bloodwork, and/or consultations that the hospitalist had ordered for that day. It took approximately 30 minutes to review 20 patients. Outlining expected roles for individuals on the multidisciplinary team as well as setting an expected date of discharge helped every member of the team understand what the plan was for each patient's hospitalization and discharge.

Using this new approach on the three wings of the fourth floor for 2 weeks decreased the LOS dramatically. The hospitalists who participated in the 2 week trial were impressed with how well everyone worked together as a team and how streamlined the discharge process became when everyone had anticipated and planned for the discharge prior to that final day. 4Macauley and 4NR eventually abandoned the hallway rounds in favor of a conference room because the halls were too crowded with upwards of 10 members of the multidisciplinary team trying to communicate with each other. Some of the nurses were concerned about patient privacy by having rounds in the hall.

One of the disadvantages of doing rounds in the conference room is that none of the floors have found a successful way to incorporate the bedside nurses into these rounds. 4 Gabrilove is the only floor that continues to do hallway rounding and involves every bedside nurse. The hospitalists believe these nurses are critical to the teamwork-focused approach because they have the most contact with the patients on a daily basis. Also, by having a set time to communicate with the physicians about patients, it gives the physicians time to get their work done after multidisciplinary rounds without being interrupted by each individual nurse.

Once the case management department is fully staffed, our goal is to reinstate multidisciplinary rounds throughout the 4th floor and expand it to the 6th floor. However, there are still 2 hospitalist physicians every day who are not assigned to a specific unit. We are working with case management to determine the best way to coordinate a teamwork approach to the care of their patients.

After having done geographic rounding for approximately one year, most hospitalists enjoy being on one floor and getting to know the nursing staff better, and having more frequent interactions with the patients and case management staff. In addition, the hospitalist is in one location so they can speak with consultants when they come by to see the hospitalist's patients. Subjectively, patients seem pleased that the doctor is more readily available to answer questions when their family members arrive, or to give them test results as soon as they're back. Nurses seem to like having a doctor to run questions by about their patients that they normally wouldn't page the physician for. Overall, there is more communication occurring between all members of the team and that, in turn, is leading to improved patient care.